Learning to Code before LLMs

The standard advice when I was a new engineer for learning how to code was to pick a project you really wanted to do and try to make progress on it. I found this supremely unhelpful, because if I threw out some ideas, it would turn out everything I wanted to make was not beginner-friendly (“you need a database for that! you’d have to figure out graphics!"). When you’re truly a beginner, sizing tasks is hard. (Let’s be real, sizing tasks is always hard.) And for me, writing software has always been a fundamentally social activity. I want to build things that others will want to use.

Which is how I developed my actual advice for programmers who are just starting out and looking for approachable but useful software projects; find someone who is doing something bananas and painful in a spreadsheet, and automate it. This is ubiquitous. Lots of actual software companies start this way. Early in my career I worked as a “project manager” for non-profit tech projects and 90% of the job was asking people to show me their weird and taxing excel processes. A vineyard once paid me in wine to design them some linked spreadsheets for tracking samples. Throw a stone and you’ll hit a business, even today, putting stuff in excel that could actually benefit from more dedicated software.

Projects to automate manual spreadsheet work are not just approachable, but hit a lot of entry level tasks. File handling, string manipulation, basic math. You also get the experience of requirements gathering as you ask questions. And in the end, you might get a gift card or acknowledgement in a research paper because the script you cranked out actually helped someone.

Science and Side Projects

I found a lot of my side projects like this in the context of problems my husband faced at work. In grad school, one of his good friends working in another lab needed a better way to format data than “manually copy individual values into cells”. In a couple of hours, I threw functions into an iPython notebook (because it was easy for the folks in the lab to install Anaconda) that eventually became a lab training for other scientists: PlateReaderHelper. If you follow that, you won’t find beautiful code. But you will find something valuable enough for awhile for friends that they trained their whole lab on it.

A couple of years ago, my husband told me his employer was planning to devote 2 junior scientists to copy/pasting molecular databases from public websites. I was writing Ruby in my job at the time, and saw it as an opportunity to play with Nokogiri. This served their purposes, and I got a free gift card for dinner. The junior scientists got to spend their time on something more rewarding than hitting CTRL-C + CTRL-V for months. These kind of little wins always reinvigorated my sense of joy in building software.

Recently though, my husband has started teaching his colleagues how to do this work themselves using LLMs. As I’ve explored how to use and get better with AI tools, image generation, and MCP servers for software engineering, I’d frequently turn to him and ask “hey, are you using this? how?” At first the answer was no, and it became pretty clear why as we worked side-by-side; the models and frameworks I had access to were much more contextually rich and embedded in my existing tools. They also were quicker to give me useful outputs.

Reality Check: Science is Hard

To start, my husband chose a project where he’d already done most of the work over a quarter and asked the question “how could I have done this faster if I used AI?” This is a departure from a lot of the corporate AI initiatives circulating in biology and chemistry. Many people have pitched ambitious projects which are difficult largely because they don’t have good data.

There’s an old quote from Chomsky:

Science is a bit like the joke about the drunk who is looking under a lamppost for a key that he has lost on the other side of the street, because that’s where the light is.

Right now, using an LLM gives you a WAY bigger lamppost. Maybe it happens to illuminate the other side of the street. But a lot of organizations seem to think it’s going to propel novel discoveries rather than enabling more efficient referencing of known information. You still gotta do the research.

Lack of quality data is going to be a problem in a lot of spaces I imagine. Software engineers have been obsessed with green tiles for decades. There seems to be a huge overlap between “software engineer” and “quantifying things for fun”. At a conference, I learned a local engineering leader at one point built software to track the productivity of his backyard chicken coop. This kind of thing does not happen broadly at the rate the people who do that kind of thing (engineers) are inclined to imagine. It wasn’t that long ago that physical lab notebooks went out of style, and lab sciences frequently struggle to this day to come up with accessible ways to format and track research endeavors.

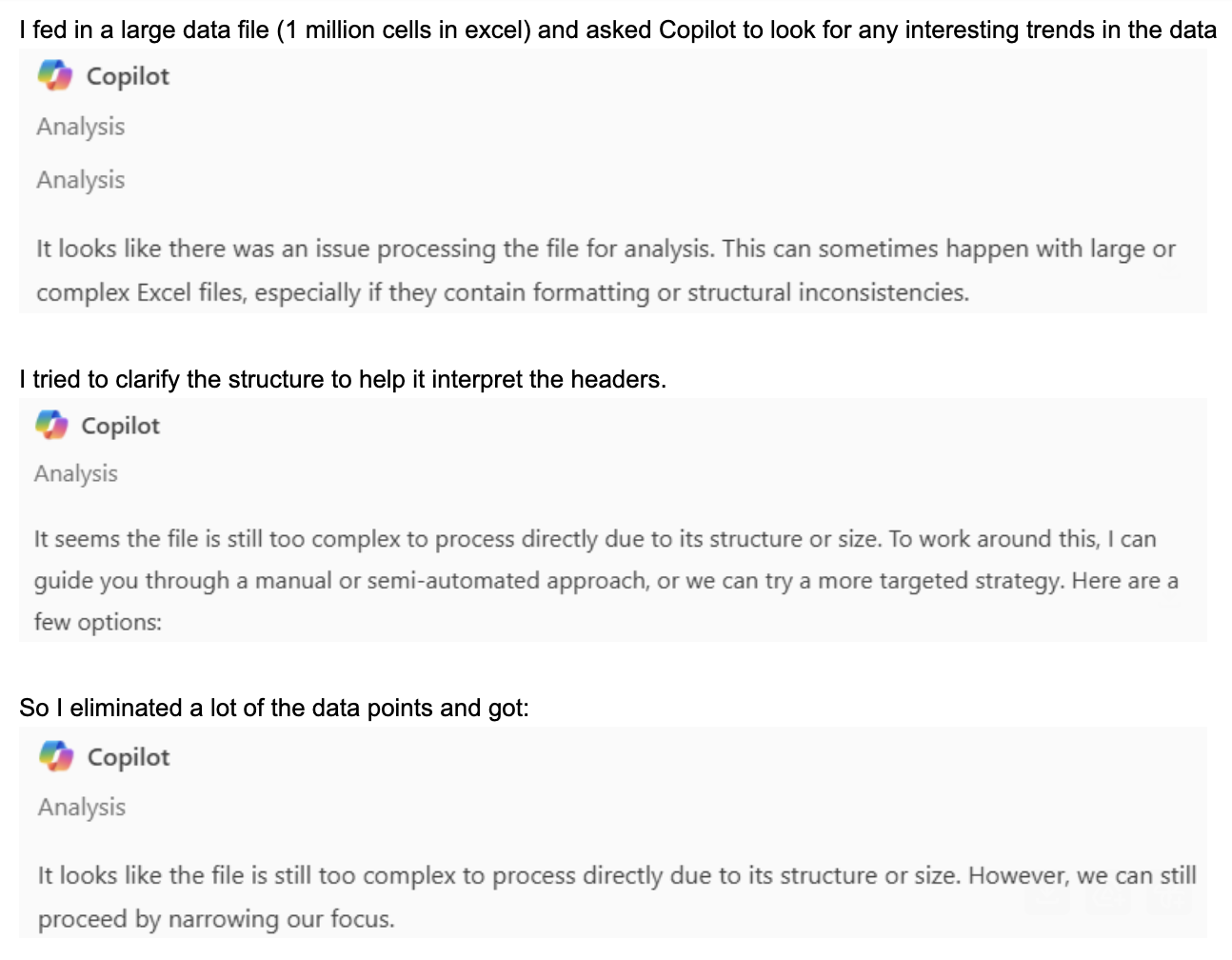

So when Adam asked Copilot to do his job, Copilot replied “your job seems kind of big and complex, please make it smaller”:

He ended up looping with it like this for awhile; every time he tried to reduce scope by cutting out data points or attributes, it wasn’t enough.

And then:

Finally he realized he could get something useful by prompting it to chart a subset of the data in a particular way as a heatmap; a manual task he’d done as part of the overall project analysis. And it worked! It gave him a visual that had been key to a turning point in the understanding of the research.

“…is it correct though?” I asked - or did it hallucinate the actual data points. While the visualization matched the pattern, we quickly found all the actual values were nonsense.

Learning to Talk Like a Programmer to a Robot

After this experiment, we sat down together and I tried to summarize how I have found success using LLM tools. I mentally categorize the prompts I throw it in 2 buckets right now:

- Exploration

- Implementation

For exploration, I’ll tell it to pretend it’s a grizzled systems admin and to critique my infrastructure plan. Or I’ll describe a specific phenomenon and ask it to suggest patterns for optimizing that process. These kind of questions help me assess tradeoffs and serve as a shortcut for search terms that might help me hone in on a plan.

Once I know my approach, I’ll use models in my IDE to implement an example class where I can fill in the details, finish a method I started, or scaffold some unit tests (and on well organized code these pretty much work out the gate - which is incredible!) Essentially, scaffolding, or sometimes mid-loop solution generation.

I toggle between those states and am very significant in navigating between them, making decisions and sometimes telling Copilot “you’re drunk, go home.”

I’m not sure the categories are the same for a research scientist, but talking about it led me to point out “a lot of your problems and time are automation problems, and you’re skipping to the solution.” I suggested he play around with asking it to write code (python scripts, an excel macro, whatever!) with a defined input and output to accelerate how he interacts with data as maybe being a more useful way to prompt.

He messaged me the next week - it worked! In a few minutes, he was able to create a python script that did the opposite of my PlateReaderHelper from a decade ago. For his particular problem, he wanted to see the data laid out as a heatmap by plate well, but his current experiment data was more normalized. Microsoft Copilot easily gave him the tools to look at his data in another way.

Democratization of Code

To me, this is huge and aligns with what I hear from some of the folks most excited about AI. For one-off code tasks, LLMs really do give you an incredible boost. The speed with which I can prototype standalone code is amazing. And why shouldn’t non-engineers be able to approach their own problems with code?

“If everyone can create software, that’s mindblowing!"

Steve Yegge predicts a proliferation of startups. “The calculus doesn’t look in favor of big companies beefing up further.”

The future seems like one where we are enabling more people to write some code. But those people aren’t software engineers and probably aren’t interested in learning sql or git.

I have a story I’ve told a lot of friends in tech. When I first was learning to code, I joined a PyLadies meetup. The group held an intro coding class at a local library, and when we went around and gave introductions there were 2 teachers. As they introduced themselves, they revealed that the main reason they had come was that their attendance software was so bad - and their IT admins so rude - that they felt like learning to program and build their own attendance software was their most feasible path to being able to do this very basic part of their job.

Intuitively, I think we all know this is true. But I’ll meet software engineers who say “what I do doesn’t matter, not like teachers.” You all; teachers use software. When software is well suited to the things they need to accomplish, it makes their lives easier and gives them time back to focus on things they care about more. It lets them focus on higher-order problems.

How We Do This: Left As an Exercise for the Reader (who is probably some kind of programmer?)

Watching this flow, I have so many ideas and questions about the next big problems I feel like we need to address. Steve Yegge talks about guardrails and tests being critical when working with agentic AI; LLMs can help us with this too, because unless you work in big tech my experience is that most software companies are operating without a lot of these guardrails. But while I am more optimistic about LLMs than the author, I want to quote this from I Will Fucking Piledrive You If You Mention AI Again which I saw shared around a lot about a year ago:

Most organizations cannot ship the most basic applications imaginable with any consistency, and you’re out here saying that the best way to remain competitive is to roll out experimental technology that is an order of magnitude more sophisticated than anything else your I.T department runs, which you have no experience hiring for, when the organization has never used a GPU for anything other than junior engineers playing video games with their camera off during standup, and even if you do that all right there is a chance that the problem is simply unsolvable due to the characteristics of your data and business?

So in an industry where we are still struggling to understand and adopt best practices - how do we start evolving our platforms to enable non-developers to take advantage of those same nascent concepts? I feel like there is going to be a wave of products that require the existence of a strong platform to empower domain experts in adding on their own custom features. But when you start enabling non-engineers to engineer…that’s a different scale of problem. We’ve already been struggling to do that in a meaningful way with low-code solutions.

I hope it’s going to push us to come up with better ways of approaching what we do. And I’m, on the whole, really excited about that possibility. Am I concerned about societal harm? Yes. But most of the dangers I see aren’t new; these are trends that kicked in before I ever wrote my first “hello world”. I feel like at the end of the day, I can’t hate an evolution in technology that makes it easier to create software without believing we already have good software.

I hope some teachers start coming for EdTech, because building applications no longer means they have to take my route with a masters degree and 15 years of experience before they build their thing. Let’s get some doctors to rethink EHRs. Maybe someone will give scientists analytics tools that meet them in their problems. This capability isn’t going away, but maybe we can make it an enabling one rather than a replacement for skilled individuals. We know software is better when users are a driving voice in the design.